“More valuable than gold, its secrets known to very few, and no one outside the Ishian River valley.”

The above line, from Argren Blue, describes the blue pigment of the title. It seems farfetched that a pigment could be more valuable than gold. But, in fact, ultramarine, the blue pigment for hundreds of years was, literally, more valuable than gold. The history of blue pigments is filled with such stranger-than-fiction facts. It’s a story steeped in alchemy, intrigue, espionage, exploitation, oppression and fortunes made.

I first became interested in the color blue when I read that some scholars believed peoples of ancient civilizations couldn’t see the color blue. I was sure it had to be one of those urban legends that can only gain credibility in the Internet era. But it turns out it was a serious academic theory that originated when a scholar counted all the color words in Homer’s Illiad and Odyssey and found exactly zero instances of blue. Not once in 1700 pages is blue mentioned, not even when he described the sea or the sky. This is true of other ancient documents as well.

As absurd as it sounds, this led some scholars to speculate that the ability to see blue was a recent evolutionary development. The debate raged for years, as only academic debates can. Although not completely settled, the predominate theory is that some cultures simply don’t name colors the same as others. It turns out there are cultures in modern times that have no word for blue. So, it’s not the case that people couldn’t see the color blue, it’s just that they didn’t distinguish blue from green, for example.

The first artificial blue pigment was Egyptian blue, created by the… uh… Egyptians. The process required to create it was so complex that it boggles the mind how they managed to discover it. Egyptian blue was around long enough for the Romans to comment on it, but the process to create it was eventually lost for hundreds of years before being rediscovered recently.

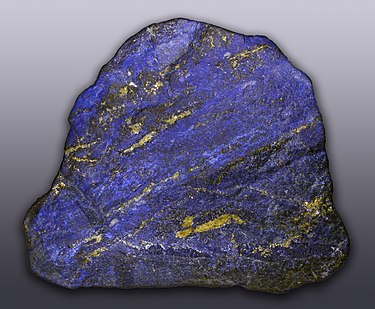

The next great blue pigment, ultramarine, the one which artists complained was more valuable than gold, appeared in Europe around the 5th century. Its cost was due to the fact the it was so difficult to produce. It was made from lapis lazuli, a stone only found in what is now Afghanistan. Although the stone is blue, if you simply grind it into a powder, it turns gray. Turning it into a vivid blue pigment requires another laborious and complex process. Again, you have to wonder how they discovered it and how many other things they tried in vain.

True blue pigments are quite rare in nature. Wander the produce aisles of your local grocery store and count how many blue things you see. There are blueberries, of course, but they are more a deep purple than blue. So, creating a blue pigment from natural sources is difficult.

So, most blue pigments are created artificially. Unfortunately, it turns out it’s nearly impossible to predict whether a given mix of chemicals will produce the color blue. Blue pigments are invariably discovered more through serendipity than intent. For example, the blue pigment that supplanted ultramarine as the most commonly used pigment, Prussian Blue, was discovered when a chemist was trying to make a red pigment and used a contaminated ingredient. This was in the early 18th century, but the situation hasn’t changed in modern times. YInMin Blue was discovered in 2006 when a chemist was studying materials for electronic applications. It was the first inorganic blue pigment discovered in over 200 years and caused enough of a stir to inspire a music festival and a new crayon by Crayola.

Another blue pigment familiar to almost everyone is indigo, because it is used to dye blue jeans. In Europe, indigo was originally created using a plant called woad. This was the pigment the Romans encountered when they invaded Britannia. Julius Caesar wrote, “All the Britons’ indeed, dye themselves with woad, which makes a blue color, and makes their appearance in battle more terrible.”

Hundreds of years after the Roman Empire fell, woad was supplanted by plants of the Indigofera species. The blue pigment from woad had become so important to European economies that royal decrees were issued in multiple countries to prevent the use of new plant. Of course, when fortunes are at stake, it’s hard to hold back progress. Eventually, Indigofera was grown on vast plantations worked by slaves in various parts of the world. The story of Indigo could fill books.

The story of the color blue and blue pigments is fascinating. I can’t truly say how it came to be at the center of Argren Blue. I remember the conversation with my coauthor at our local brewery, the Black Husky, when we hit on the idea. I even remember where we were sitting and what I was drinking. But the conversational path that led to the idea is lost to me. Oh well. In any case, I hope the fact that the story of pigments at the heart of Argren Blue is ripped from history adds an intriguing element to story.

But what is Argren Blue? Which of the star blue pigments from our history is closest? It’s up to the reader. Deb sees Maxfield Parish blue. I see — I prefer to keep that a secret.

If I’ve piqued your interest, you can find the full story, or a big part of it, in Blue by Kal Kupferschmidt.

(All the images are from Wikipedia)

1 thought on “A Nerdy take on Argren Blue”

Love it, Ross! I wondered if there wasn’t something like this behind it when I read Argen Blue.

Comments are closed.